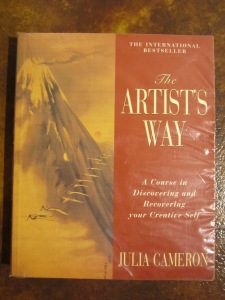

It’s twenty years since I first read The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron – a book that I believe led directly to my becoming a writer. My process wasn’t a fast one, but the book awakened an unspoken ambition that had lived within me since childhood: the creation of worlds in the imagination, and making up stories for other people to read.

There are two key points about doing The Artist’s Way. (Yes, it’s not just a book that you read; it is a 12-week course in which you uncover the artist within you, layer by layer, chapter by chapter, week by week, and start to bloom into the artist you were meant to be.)

The first of these key points is a thing called Morning Pages – a stream of consciousness writing of three handwritten A4 pages every single morning when you wake up, before the world intrudes.

The second is a weekly Artist Date – a treat that you give the artist child hiding within your jaded adult self. This usually takes the form of going somewhere special on your own, to soak up or explore something wondrous and adventurous. It needs to be something that lifts your spirits, fills the creative well inside you, and inspires you to continue your art with renewed passion.

I’ve been doing morning pages for twenty years now, and they are still as valuable as ever, even though I made the switch to doing them on my laptop five years ago. But the Artist Dates? I’m not sure when I realised they had dropped off my radar. Sometimes, when I am on leave, I spend a day doing something different, all by myself, and I remember again how much fun it is to take myself on an Artist Date. But I only ever seem to do that once every three months or so.

Yesterday, however, I went on an exceptional Artist Date.

Three days ago I googled the Museum of Modern Art because a Facebook friend in America had written about it. I was surprised when Google showed me another Museum of Modern Art – one in my hometown in Australia, and a place about which I had never even heard. If not for the similarity of the name with the American one, I might never have found it, and that would have been such a pity.

The Heide Museum of Modern Art is in north-eastern Melbourne, almost an hour’s drive from where I live. It is set in 16 acres of beautiful parkland which used to be a dairy farm a hundred years ago, in an area called Heidelberg. In the 1930s it was bought by John and Sunday Reed, who borrowed and shortened the suburb’s name to call their home Heide.

They had two cows which John milked every morning. Sunday planted a kitchen garden in which she grew everything they needed to eat, and they threw open their modest farmhouse (see below) to many, many artist friends.

Before long, it became an artist colony: the Heide Circle. Those who stayed there helped with either the milking or the gardening, in exchange for a space in which to grow their art.

In time, the farmhouse became too small for all the art, so the Reeds commissioned another building on the same property – one in which they would be able to live, and which could later be turned into a second gallery. They moved into it in the 1960s, and called it Heide II – see the picture on the left. Their old cottage was now affectionately known as Heide I.

Twenty years later, by the time John’s health began to fail, they turned Heide II into the gallery it was meant to be, and moved themselves back into Heide I.

Heide II officially opened as a gallery in November 1981. John died a few weeks later, and Sunday followed ten days after him, unable to bear life without John.

The legacy they left is enormous.

There is now a third, larger and more modern, gallery called – what else? – Heide III. See photo at right.

The whole complex is known as the Heide Museum of Modern Art, and all three buildings are in constant use as gallery space. In addition to the three galleries, there is a café, a gift shop, and the entire garden is a sculpture park.

The park is used for other things too, and it was one of these activities that drew me to it. On Thursday mornings they have Tai Chi in the park, under the trees. When I googled it on Tuesday, and saw that I could join the class, I decided to make a day of it.

What a wonderful day it was too!

Our Tai Chi class was held beneath the huge tree on the left of the picture alongside, watched over by several sculpted cows, reflecting the property’s original purpose as a dairy farm.

After the class, I wandered about the grounds, looking at other sculptures, as well as the two kitchen gardens planted by Sunday, which today provide everything that is required to equip the café with its excellent lunch menu.

As the heat of the day set in, I found myself closest to Heide II, so I started my indoor exploration there. To be honest, I was far more fascinated by the actual building than the exhibition in it. I walked through, imagining the Reeds living in this cool white space – their bedroom, study, cosy conversation pit, and a sunken lounge downstairs with enormous glass walls revealing more sculpture courtyards shaded by ancient trees.

Next I visited Heide III, and lost myself in the Albert & Barbara Tucker gallery, where I saw many paintings and photographs from Tucker’s life when he toured Europe in a home-made caravan in the 1950s. His letters back to John and Sunday were also on display, documenting his progress as a painter, along with his gradual, somewhat reluctant, return to his Australian roots after many years on the road.

On my way to Heide I, I passed John Reed’s old milking shed – see the photo on the right – which is next on the list for restoration.

Finally, I reached Heide I. Somehow I had sensed that this would be the place I would enjoy the most. This little house, now beautifully restored, encapsulated the history of the people who lived there and did so much for Australian art and artists.

It is a gallery, but it is also a museum, preserving something of the lives of its former inhabitants. It contains many poignant remnants of its colourful past.

For example, the small library – the window on the right of the photo below – is exactly as it used to be in the days when displaced Russian painter Danila Vassilieff used it as his painting space, and he later died in that room while on a visit.

Artist Sidney Nolan began his series of now-famous Ned Kelly paintings on the Reeds’ dining table. Artist Mary Perceval hand-painted 22 small tiles with different pictures of cats, and presented them to Sunday Reed to decorate her kitchen, because she knew how much Sunday loved cats. The tiles are still there above the fireplace in the kitchen.

Walking through the spaces where Sunday used to hold informal afternoon tea parties, looking at the photographs all over the walls, and admiring the beautiful cat tiles in the kitchen, I felt an affinity with this place that nurtured artists and provided them with both the space and the inspiration to do their best work. I do believe that some hint of their combined artistic presence still lingers there amongst the framed paintings, photographs, letters and sculptures.

It wasn’t until I sat in the café at 2:00 pm that I realised I was actually on a full-length Artist Date. And I never wanted it to end. I don’t paint and I don’t do sculpture, but I became completely wrapped up in the story of the Reeds and their artist companions, the photography and stories on display, the wonderful history of the place, including the actual buildings. So much so, that I now feel inspired to return to my own chosen art – that of writing. I have neglected this of late, but I vowed yesterday that I will make time to continue my passion for writing, and I will definitely finish that novel…

Watch this space!